Friday, January 04, 2019

Business as usual will no longer suffice…

Monday, November 19, 2018

Leveraging design to help overcome key challenges to creating shared value

- consider entire ecosystems, facilitate the meaningful participation and collaboration of many, and facilitate the alignment of purpose of multiple stakeholders;

- achieve an adequate understanding of social and environmental issues, suspending often false presuppositions in order to appropriately and creatively frame those issues;

- generate insights that identify opportunities to “reimagine social change” (and/or environmental change) and accompanying business strategy change;

- explore and test potential opportunities for creating shared value without risking damage to the social or environmental sector or a corporation’s reputation.

Friday, October 21, 2016

Do I really need to write a book?

- “The three-legged stool of collaboration”

- Breaking silos

- “Check your disciplines at the door” when beneficial

- The need for good facilitation

- Soft skills

- Walls

- Effective collaboration and fun

- Are you trying to solve the right problem?

- On concept design, ethnography, MRDs, and product vision

- A(other) call to action regarding healthcare

- Utilizing patients in the experience design process

- Go ahead — ask people what they want

- Applying “design thinking” to, um, design

- Prototyping for tiny fingers

- Preconceived notions

- “Designing in hostile territory”

- “There is only so much air in the room”

- Making changes to a company’s culture

- What is holding User Experience back or propelling User Experience forward where you work?

- Roles and relationships

- Eliminating noise and confusion

- Framing change / Changing frames

- Secret agent (wo)man?

- Changing the course or pace of a large ship

- Partnering with power

- Calculating return on investment

- Perturbing the ecosystem via intensive, rapid, cross-disciplinary collaboration

- Convincing executives and other management personnel of the value of ethnography

- Where should “User Experience” be positioned in your company?

- Does it matter where User Experience is positioned in your corporate structure?

- On the importance of alignment, trust, loyalty, …

- Hail to the Chief!

- Getting the organizational relationships right

- Ownership of the user-customer experience

- The internal consultancy model for strategic UXD relevance

- Who should you hire?

OK, maybe I should write a book. But while I do that or consider doing that, look through the lists of posts I've presented above for those that might be of help to you now. Use the tags for help accessing others. As I mentioned earlier, even the older posts continue to be of relevance.

Saturday, April 27, 2013

What designers need to know/do to help transform healthcare

I've been immersing myself in all things focused in some way on dramatically changing the U.S. healthcare system and the patient experience. This has included attending lots of events. Last week, I attended the Health Technology Forum Innovation Conference. Two weeks ago, I attended the Second Annual Great Silicon Valley Oxford Union Debate focused on whether Silicon Valley innovation will solve the healthcare crisis. Near the end of March, I attended both a panel discussion about "Improving the Ethics and Practice of Medicine" and hxd (Healthcare Experience Design) 2013. ... (The list goes on and on.)

I've also been writing and speaking about this topic as well. Recent examples include the blog post I wrote for interactions in December entitled, "The Importance of the Social to Achieving the Personal" (in healthcare) and my presentation at hxd 2013 entitled, "Preventing Nightmare Patient Experiences Like Mine" (subtitled, "Avoiding 'Putting Lipstick on a Pig'").

I've also been writing and speaking about this topic as well. Recent examples include the blog post I wrote for interactions in December entitled, "The Importance of the Social to Achieving the Personal" (in healthcare) and my presentation at hxd 2013 entitled, "Preventing Nightmare Patient Experiences Like Mine" (subtitled, "Avoiding 'Putting Lipstick on a Pig'").As most agree, the U.S. healthcare system and patient experience are badly in need of disruptive innovation, a transformation, and/or a revolution. Hence, the subtitle of my hxd 2013 presentation implies that there are things (UX) designers need to be aware of or do (or not do) so that they can do more than only contribute to modest improvement of the status quo.

What are those things? The things I addressed in that presentation:

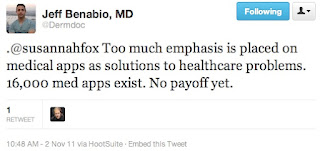

- too many designers are too enthralled with technology and too focused on digital user interfaces to have a great impact on transforming healthcare;

- human-centered design as often practiced is better suited for achieving incremental innovation instead of the disruptive innovation most needed -- Don Norman and Roberto Verganti have written a great essay about this;

- design research too often falls short of revealing the nature and dynamics of the socio-cultural models at play that need to change;

- design research too often focuses on common cases instead of the "edge" cases which can more identify or reveal emergent and needed innovation;

- essential to solving the "wicked problem" of healthcare is reframing it, something not all designers do adequately -- Hugh Dubberly and others addressed this particularly well in an interactions magazine cover story;

- designers need to get picky about the kinds of healthcare projects they work on.

What would you add to this list? Is there anything in the list you question? Let's have a conversation. Please comment below or contact me via email at riander(at)well(dot)com.

And if you hear of any events you think I might be interested in attending...

Monday, January 28, 2013

On what holds UX back or propels UX forward in the workplace

Among the teaching that I've done: UX management courses and workshops via the University of California Extension, during conferences, and in companies. And a topic I have always addressed therein: what holds UX back and propels UX forward in the workplace -- or to put it another way, what increases and what decreases the influence of UX on the business.

Last month, Dan Rosenberg authored an interactions blog post in which he states that a root cause for a lack of UX leadership in business decisions relates to "how the typical types and methods of user research data we collect and communicate today have failed our most important leadership customer/partner/funding source, the corporate CEO." (Dan will be elaborating on this in the March+April 2013 issue of interactions.) In my courses and workshops, we identify all sorts of reasons UX isn't as influential as it might or should be, and we often do so in part via use of a simple "speedboat exercise" as I described in a UX Magazine article entitled, "What is Holding User Experience Back Where You Work?". (A variation of the exercise can be used to help identify what has propelled UX forward in workplaces.)

I've also often addressed this topic in my blog, sometimes referring to discussions that occurred during my management courses or during conference sessions. For example, course guest speaker John Armitage made the following point:

"There is only so much air in the room -- only so much budget, head-count, attention, and future potential in an organization. And people within the organization are struggling to acquire it -- struggling for power, influence, promotion, etc. whether because of ego or as a competitive move against threats of rivals. People will turn a blind eye to good ideas if they don't support their career and personal objectives. Hence, if user experience is perceived as a threat, and if they think they can stop it, they will, even if it hurts the company."Guest speaker Jim Nieters addressed the role that the positioning of UX personnel in an organization plays:

"You want to work for an executive who buys-in to what you do. If that executive is in marketing, then that is where you should be positioned. If that executive is in engineering, then that is where you should be positioned. Specifically where you sit matters less than finding the executive who supports you the most. If the executive you work for has reservations about what you do and wants proof of its value, that is a sign that you might be working for the wrong person."Organizational positioning and the type of user research conducted were two of the factors debated by a stellar panel of UX executives and managers I assembled for a CHI conference session entitled, "Moving User Experience into a Position of Corporate Influence: Whose Advice Really Works?".

We also addressed this topic in interactions articles published when I was the magazine's Co-Editor-in-Chief. For example, in "The Business of Customer Experience," Secil Watson described work done by her teams at Wells Fargo Bank:

"We championed customer experience broadly. We knew that product managers, engineers, and servicing staff were equally important partners in the success of each of our customer-experience efforts. Instead of owning and controlling the goal of creating positive customer experience, we shared our vision and our methods across the group. This was a grassroots effort that took a long time. We didn't do formal training across the group, nor did we mandate a new process. Instead, we created converts in every project we touched using our UCD methods. Having a flexible set of well-designed, easy-to-use UCD tools ... made the experience teams more credible and put us in the position of guiding the process of concept definition and design for our business partners."Forming the centerpiece of their UCD toolkit: an extensive user research-based user task model. The influence of the use of these tools extended to project identification, project prioritization, business case development, and more.

I encourage managers to employ the speedboat exercise to prompt diagnosis and discussion in their own place of work. Also, peruse my blog posts and past issues of interactions for more on factors that impact the influence of UX. And give particular thought to the role user research might play; along these lines, look forward, with me, to what further Dan Rosenberg has to say in the March+April issue of interactions.

Monday, April 30, 2012

A(nother) call to action regarding healthcare

"Given the current power of CX at the C-level, UX practitioners must step up our game, otherwise we will lose progress we have made to be more deeply involved in strategy beyond just performing usability services. We need to act now to be part of the broader CX solution. If we don't proactively collaborate across divisions and organizational structures, we will be stuck playing in the corner by ourselves. If we don't figure out how to manage partnerships with other departments in a collaborative, creative, customer focused way, the discipline of UX as we know it is at risk. CX management will take over."

"UX design has done a great job in the last decade of redefining (for the better) how we define requirements for products with digital UIs. There is no doubt about this. But this has come at a cost of upward mobility in our organizations. We're functional players that make tactical work more efficient. We're not strategic players that help our organizations transform themselves. The closer we look at UIs, the more pigeonholed we're likely to be.

...stepping up [to strategic challenges] may mean stepping out of our comfort zones. ...we can't go in waving deliverables -- our standard bulwark. We have to step out from behind our wireframes and prototypes and think strategically."

"Health care is broken. ... We have set up a delivery system that is fragmented, unsafe, not patient-centered, full of waste, and unreliable. Despite the best efforts of the workforce, we built it wrong. It isn't built for modern times."

"We call individuals 'patients.' We call physicians healthcare 'professionals' (HCPs). Professionals 'care for' patients -- by observing symptoms, diagnosing diseases, and proposing therapies. Their proposals are not just suggestions: they are prescriptions or literally 'physician orders.' Patients who don't take their medicine are not 'in compliance.'

In the relationship between HCPs and patients, HCPs dominate. HCPs do whatever is necessary, with patients playing a relatively passive role. In some ways, the system reduces patients to the status of children -- simply receiving treatment."

"Going to the doctor, having routine surgery, buying bulk medications online -- all could be radically reinvented with the application of one type of medicine: designed disruptive innovation. Combining the principles of disruptive innovation with design thinking is exactly what health care in America needs. We need to disrupt the current business model of health-care delivery. And we need these disruptions to be designed experiences that are consumer-focused."

Tuesday, January 31, 2012

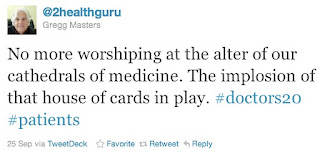

No more worshiping at the altar of our cathedrals of business

A version of this article was published in the January+February 2012 issue of interactions magazine.

I've been reviewing an excellent manuscript for a book on design thinking and reading about a new game and kit developed by IDEO to help explain it. These things delight me, since for years, I've been focused on expanding the role of design/UX to be a full participant in defining business strategy and in being a catalyst for that change. More recently, participation in defining social strategy became an important part of that focus. Design thinking came to be advocated by business visionaries to be a major part of a fix to a broken strategy definition process. Jon Kolko and I published our and others' writings about such things in interactions when we were Co-Editors-in-Chief.

So, I have been intrigued by proclamations that design thinking is a failed experiment, that it is misguided to attempt to describe the process, and that design thinking must be recognized as the purview of the trained designer. Innumerable attempts at explaining the usually less ambitious "user-centered design" have been greeted by similar negative reactions over the years.

Just what is going on here? Why the negative reactions? Sometimes stepping aside to look at comparable happenings in a seemingly different context can provide some insight, so allow me to describe some of what is happening in the world of healthcare.

In today's world of healthcare, a ballooning number of patients seek at minimum full participation in defining their diagnostic/treatment strategy. Why? Because of an outrageous number of medical misdiagnoses, because of what is often an insulting patient experience involving doctors who don't listen to or even bother to touch their patients anymore, because doctors tend to just "regurgitate (knowledge) rather than think" and disregard limits to their knowledge and experience, because a system of referrals and approvals prevents direct and ready access to doctors with needed expertise, ... -- in short, because of a healthcare system declared to be "broken" by speaker after speaker at Medicine 2.0'11 held at the Stanford University Medical Center.

Patient efforts to meaningfully pierce the diagnostic/treatment process have been greeted with claims that patients lack the skills/training to do this successfully, that only doctors can diagnose and prescribe correctly, that anything patients learn via the internet is highly suspect, that reducing diagnosis/treatment to a process in which patients can participate ignores the fact that the practice of medicine is as much of an art as a science, ... -- reasons coming from members of a community (i.e., doctors) classified as a stage 3 (of 5) tribe: "I'm great, and you're not."

You should be seeing a lot of parallels...

In spite of proclamations against greater participation of patients, the "epatient" movement is growing rapidly, with peer-to-peer healthcare increasingly seen as an essential part of a fully functional healthcare system in which social media play vital roles. A Society for Participatory Medicine has been formed as part of this movement "in which networked patients shift from being mere passengers to responsible drivers of their health, and in which providers encourage and value them as full partners." I'm even seeing suggestions of a need for an "Occupy Healthcare" movement. Meanwhile, medical rebels such as Jay Parkinson are showing how a patient-centered healthcare practice can work in spite of active resistance from the medical community, and programs are being designed to train medical students how to listen and talk to patients.

The following observation by an attendee of Health 2.0 San Francisco 2011 speaks to all of this:

And as I write this, the Occupy Wall Street protests are going global. As Thomas Friedman states in The New York Times:

"Occupy Wall Street is like the kid in the fairy story saying what everyone knows but is afraid to say: the emperor has no clothes. The system is broken."

Indeed, the businesses in which many of you work are broken, operating and/or structured in ways more appropriate for an earlier era. Many of these businesses are faced with the need to become genuninely user- or customer-centered and connected/social. To achieve this, design/UX leadership is badly needed. However, as Samantha Starmer warned after learning that design/UX personnel are not the ones getting the many newly created Chief Customer Officer positions:

"Given the current power of CX at the C-level, UX practitioners must step up our game, otherwise we will lose progress we have made to be more deeply involved in strategy beyond just performing usability services. We need to act now to be part of the broader CX solution. If we don't proactively collaborate across divisions and organizational structures, we will be stuck playing in the corner by ourselves. If we don'f figure out how to manage partnerships with other departments in a collaborative, creatice, customer focused way, the discipline of UX as we know it is at risk. CX management will take over."

New social, user/customer-centered businesses are needed. "Citizen-centered" social strategy is needed. And design (thinking) can lead the way.

Describing/explaining the design process for others to understand -- to enable their effective participation -- is essential for this to happen. However, more educational programs akin to that provided by the Austin Center for Design are needed. Perhaps a new professional association -- a resurrection of a sort of Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility -- fully focused on this kind of participatory design would be helpful.

We've reached the point of no more worshiping at the altar of our cathedrals of business. The marginalization of design (thinking) and UX is finally on its way to the rag pile.

It is a very good time to be a design( think)er.

Thursday, March 10, 2011

Impact of the role of the Chief Customer Officer

Forrester Research's initial advocation of the creation of the role in 2006 referred to it as a CC/EO -- a Chief Customer/Experience Officer. Subsequently, the word "Experience" in the title lost favor, and creation of the role of the Chief Customer Officer has taken off. There is even a (somewhat dated) book available about the role and a member-led advisory network of CCO peers.

Who is filling these roles? According to Forrester's Paul Hagan:

"The majority are internal hires who have a significant history at their companies: median time at their firms among those we studied is nearly eight years. A third of the CCOs previously held division president or general manager roles, and almost as many worked in a marketing and/or sales position. On the flip side, about one-fourth of these CCOs formerly held operations positions."As noted by Samantha Starmer in UX Magazine, UX people are not the ones getting these newly created C-level positions. Plus, all sorts of departments are expected to be scrambling to play a major role in customer experience (CX) moving forward. This has prompted Samantha to warn:

"Given the current power of CX at the C-level, UX practitioners must step up our game, otherwise we will lose progress we have made to be more deeply involved in strategy beyond just performing usability services. We need to act now to be part of the broader CX solution. If we don't proactively collaborate across divisions and organizational structures, we will be stuck playing in the corner by ourselves. If we don't figure out how to manage partnerships with other departments in a collaborative, creative, customer focused way, the discipline of UX as we know it is at risk. CX management will take over."In her article, Samantha emphasizes the need for UX to partner with marketing, an entity with which UX has had a strained history. Such partnerships have the potential to work wonderfully well, as suggested by the successful merger of user experience research and market research to form a Customer Insights organization a few years ago at Yahoo! (see "User (experience) research, design research, usability research, market research, ..." and "Why Designers Sometimes Make Me Cringe").

Partnership with organizations other than marketing is also important. Successful examples, led by UX, include those described by Secil Watson in "The Business of Customer Experience: Lessons Learned at Wells Fargo" and me (and others) in "Improving the Design of Business and Interactive System Concepts in a Digital Business Consultancy" and "Perturbing the ecosystem via intensive, rapid, cross-disciplinary collaboration."

How do you partner successfully? Genuine collaboration is a key, and the keys to collaboration are many, as I've addressed in past blog entries. See, for example:

- "'Check your disciplines at the door' when beneficial" (also in UX Magazine);

- "Soft skills" & "The need for good facilitation";

- "Breaking silos" & "What to do about those organizational obstacles";

- "Work space" & "Walls";

- "'The three-legged stool of collaboration'";

- "Effective collaboration and fun";

- & "Collaboration sessions."

All of this and more -- e.g., getting UX moved from a cost center to an investment center (Brandon Schauer, MX 2011) -- may be essential to ensuring UX plays a vital role in the ballooning world of CX and CX management and to getting UX management personnel recognized as among the stronger candidates to fill the CCO role.

---

For more, see "Audio and slides for 'Moving UX into a position of corporate influence: Whose advice really works?'", "Ownership of the user-customer experience," and "Where should 'User Experience' be positioned in your company?".