I've interviewed many people -- individuals and pairs -- on stage, including Doug Engelbart (with Tim Lenoir), Alan Kay, Bill Buxton (once with Cliff Nass, once with Mitch Kapor), Sara Little Turnbull (three times, once with Stephanie Yost Cameron), Clement Mok & Jakob Nielsen, Joy Mountford, Paul Saffo & Jaron Lanier, Alan Cooper, Don Norman (four times, once with Janice Rohn), Bill Gaver & Wayne Gray, and Bill Moggridge. (Transcripts of the only three interviews that were recorded have been published in interactions magazine.) I've also moderated several panels of three or more people.

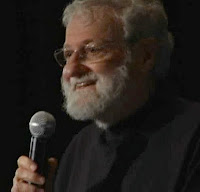

However, the best of these, for multiple reasons (some very personal), might have been the most recent: a "conversation" with Don Norman and Jon Kolko, which took place at the Academy of Art University (AAU) in San Francisco the evening of September 30, 2011. The ~2-hour exchange with and between Don and Jon and the audience (comprised mostly of AAU students) was particularly engaging, thoughtful, rich, and delightful.

The title I gave to the event was, "Out with the Old, In with the New: A Conversation with Don Norman and Jon Kolko on Trends in the Overlap between Art, Business, and Design."

Topics addressed included the nature of and the difference between art and design, whether design should be taught in art schools (such as AAU), Abraham Maslow, usability, what design (or all) education should be like, the problem with "design thinking" courses, the destiny of printed magazines and printed books, aging and ageism, the relationship between HCI and interaction design, Arduino, simplicity, social media, Google, privacy, design research, the context in which design occurs, the Austin Center for Design, solving wicked problems, whether designers make good entreprenuers, politics, Herb Simon & cybernetics, the strengths & weaknesses of interconnected systems, and how designers should position themselves.

The video of this event appears at bottom of this posting. I encourage you grab a cup of coffee (or a beer), start the video, sit back, and enjoy. For those interested in reading some of what Don and Jon said, here are just a few of the highlights (not necessarily in the sequence in which they occurred during the session):

-------

Regarding the user experience:

Jon:

"Most people attach the experience in which they have received a thing to the thing, which makes it much more important."

"...enjoyable and pleasurable ... and magical and sexual and sensual and poetic -- these are the words I use; ... if you can encourage the more ethereal and fleeting qualities, the rest comes with it."

"Design that is discursive and has a personality -- that is intended to evoke reflection of an end user -- that is the stuff that is succeeding in the market right now, and it doesn't even have to be well-done. That is what consumers are responding to."

Don:

"Usability is important, but it is not the most important thing. There are lots of parts of (the iPhone) that are completely unusable, and you know what? It doesn't matter."

"You can have negative components, and you can have things that are difficult or aren't yet well-finished or well-developed. As long as the total experience is wonderful and your memory is wonderful -- that is what matters."

-------

Regarding the "design thinking unicorn" (as Jon called it):

Don:

"Engineers and MBAs are fantastic at solving problems, but they aren't any good at making sure it is the right problem... The difference between that and designers:" (designers explore and learn and watch people and try things, Don said, via a detailed example regarding the task of designing an automobile)

Jon:

"Now, if you get an MBA, you might take a class called "design thinking," where you will learn a bunch of design methods. You'll learn a method called, "empathy." For 4 days, you learn about empathy, and then you are now certified to be empathetic. Clearly, it can't be that reductive. The problem is not that it is being taught that way; the problem is that the MBA comes out armed with this knowledge and is managing YOU, and making more money than YOU, is YOUR boss, and is telling YOU how to do your job when they don't know how to do it themselves. I've seen that happen a lot."

Don:

"If you really want to be in control of your own destiny, go get an MBA in addition to your design (degree)."

Jon:

"Something that might make more sense is getting a public policy degree, particularly if you want to cash in on whatever this design thinking thing is and applying it in a way that is really impactful."

-------

On Google:

Don:

"Google doesn't understand people -- doesn't understand consumer products; they're all about technologies... They believe in algorithms. They don't care about people. Larry and Serge are brilliant technologists, and they believe they can solve everything with an algorithm... They don't believe in designers -- they believe in testing: we'll see what people like best. What that does is give you design by committee. What is Google's product? The product is not search; the product is not advertising. The product is you. ... They are selling you to their advertisers. Their customers are the advertisers, and their product is you. So they don't care if their products work very well."

-------

On design research, the context in which design operates, and solving wicked problems:

Don:

"You have to figure out what it is that people need, how people function, how do I put this technology so that it effortlessly fits their needs and functions well, and ideally is also really pleasurable and enjoyable."

"The problem I've discovered -- even though it makes great logical sense: how can you build something unless you really understand the population you are building it for and what people are doing and their needs? -- is there is never time. ...in thinking about that, I decided it was a bad idea to teach people to do design research first, because in reality, you never were allowed to do it."

Jon:

"A couple of things have changed or represent an alternative point of view. I worked at frog for about 4 1/2 years, and when I started, we had a design research practice that was small. When I left, companies were hiring us to do design research engagements -- 4 or 5 hundred thousand dollar engagements -- where all we did was do design research. ...what changed was the relationship between empathizing with end users and building something which resonates on the market, which is different than understanding the problem you are trying to solve. I think there is a subtlety there of 'I conduct design research to understand how a coffee maker works' versus 'I conduct design research to understand what it means for this person to brew coffee,' one of which is more touchy-feely, fuzzy, subjective, and interpretive. ...all of the concerns shared by Don are true, and the anecdote of the product manager saying, 'Yeah, yeah, yeah, next time you can do your great process; this time... you know what to build, just go build it' embraces the corporate structure of quarterly profits, time to market, the artificial race to get product out, build it and iterate on it, fail fast and fail frequently, ... Increasingly, I think those are all wrong, and I think they are really wrong and harmful as well, because you can take design out of the context of business and stick it in other contexts ...such as public policy and social problems... You can stick it in a lot of contexts, because it is a discipline. It is artificially embedded in the context of business, and when it is, you have to embrace the rules of business... You don't have to buy into that, though. And what I've seen is that most of the students that I run into ... don't want anything to do with that, but they don't know any other route. They are told to go corporate or go consultancy, (as if) there is no other choice. But there are a lot of other choices. All those things (Don said) are true, and that is usually the reason the right process is cut. But you don't have to buy that."

"Not all problems are equally worth solving. It seems like we've taken it for granted that every activity within the context of design is worth doing, whether it is a drinking bottle or a microphone or a website for your band. I don't know if that is true, and I'd like to challenge it and would like more people to challenge it more regularly. That is the focus of the Austin Center for Design: problems that are socially worth doing, and broadly speaking, that means dealing with issues of poverty, nuitrition, access to clean drinking water, the quality of education, ... These are big, gnarly problems, sometimes called 'wicked' problems, and it seems incredibly idealistic to think that designers can solve them -- I agree, I don't think designers can solve them. In fact, I'm not sure anyone can solve them, but I think designers can play a role in mitigating them -- a really important role because of all of the design thinking stuff that we've already talked about: the power of that can drive innovations that are making millions of dollars for companies; it seems that that same power can be directed in other ways."

Don:

"I've seen too many designers who think they know the answers to the problems of education or the problems of health or poverty or drinking water in Africa -- it is amazing how many times design students in America are solving the problems of Africa or southern Asia as opposed to the real problems we have in the United States. If you a trying to solve problems in far-away places, you are fooling yourselves if you think you understand the problems."

Jon:

"That is the easy part. The hard part is that you are exporting your value structure, and people don't want it or understand it. We talk about empathy and how it can't be taught in 40 minutes -- empathy is a long-term thing... Right now, I'm on a tear against project-based learning, because every time you have a project, the project ends, and then you go to the next one. That is true in a consultancy, too. But that can't be true if you are talking about affecting the homeless population in San Francisco, because once you form a repoire with someone, if the project ends, you still have that repoire with someone, because they are a real person."

Don:

"My favorite quote is from (H. L.) Mencken, a journalist from the 1930s: 'Every complex problem has a simple answer, and it is wrong.'"

And related:

Jon:

"The research that is done in the (HCI) academic world is focused on appropriating technology in new ways, in clever ways, in new wild and fancy ways... There's a lot of masturbation, for lack of a better word -- gratuitous use of technology just for technology's sake. If you could reign in that intellectual powerhouse, it could actually solve some problems that are worth solving -- it would be pretty incredible."

-------

More advice for designers and design students:

Don:

"You have to be true to yourself. Whether you are working as a lone designer designing chairs, or whether you're working as one of several hundred people on a team trying to (solve) some complex sustainability problem..., you have to be true to yourself. Even if you're one voice of many. If everyone had this view, your one voice gets amplified."

Jon:

"It is the best time in history to be a (good) designer, by any metric..."

Don:

"It is a great time to be a designer, because the technology world is changing rapidly in exciting ways which gives all sorts of wonderful potential. ...it is quite often that when there are economic difficulties, the exciting ideas get started."

"Don't try to be the great name designer. The total number of great name designers will always be just a handful. We need a great many designers; we don't need star designers. A star designer is a nuisance rather than a virtue."

-------

The full ~2-hour video:

---

Thanks much to Kathleen Watson, Associate Online Director of AAU's School of Web Design & New Media, who asked me to put together a session of this nature for AAU, and to Lourdes Livingston, Graduate Director of the same school. Thanks also to Susan Wolfe for the first photo appearing in this blog entry; all other still images were taken from the video.

We are planning to do more sessions of this nature at AAU during 2012. To learn of these sessions, follow me on Twitter.