Knowing I will never again use any of the papers, books, magazines, etc. that sit in several boxes I have stored in the basement, I decided that the time had come to get rid of them all.

Knowing I will never again use any of the papers, books, magazines, etc. that sit in several boxes I have stored in the basement, I decided that the time had come to get rid of them all.However, I made the mistake of looking inside the boxes.

Ah, a couple dozen unused Group Embedded Figures Tests. Ooh -- those are cool. Hmm... you never know when I'll need to find out the relative field dependence-independence of a group of guests. It might provide critical guidance regarding how to set the dinner table and seat people around it.

Just before dinner, those guests -- or just the field dependent among them -- might want to leaf through the dozens of old Gourmet magazines I have, if I were to dust them all off a bit. The field independent guests might prefer that Theory of Matrices textbook from my undergraduate days, or perhaps Introduction to Computer Organization and Data Structures: PDP-11 Edition.

During dinner, I might want to do a reading from the article I co-authored that appeared in Journal of Educational Measurement many years ago. All those reprints in the basement, which I'd be happy to sign, could make unforgettable thank-you gifts.

That proposal for additional design and evaluation work for LAWS (a Legal Agreement Writing System) that I worked on for Pacific Bell during the 80s might be just what I need to take a look at again someday. And the code for that PLATO-based "confidence testing" system that I redesigned even earlier during my career... -- well, I'm sure I would think of a good use for that right after I discarded it.

But what is this? Ugh -- a box of old issues of Communications of the ACM. Finally something I should be able to discard; nothing could be in them that I'd ever be interested in reading again (or, more likely, for the first time). But wait -- post-its protrude from the top of a few of them. Might there actually be something of remaining value in some of them, such as in this issue dated April 1994? Sure enough, the answer: "yes" (though a far more genuine "yes" than applicable to any of the items mentioned above).

The marked article: "Prototyping for Tiny Fingers," an article about the value of low-fidelity (paper) prototypes, and how to build and test them. Though published in 1994, this is still an excellent article, and is among the articles on paper prototyping that I provided to user experience personnel who worked for me at Yahoo! as recently as 4 years ago. They adopted and adapted the approach to great benefit, generating good, new designs much more quickly (though much more intensely) and resolving old design problems that had long haunted them.

The article was written by my friend Marc Rettig, who was perhaps the first Chief Experience Officer in the world (though years after he wrote this article). Yesterday, I decided to check in with Marc about the article. Here is what he had to say:

The article was written by my friend Marc Rettig, who was perhaps the first Chief Experience Officer in the world (though years after he wrote this article). Yesterday, I decided to check in with Marc about the article. Here is what he had to say:"It has been really surprising to see how long that piece has remained useful to people. I've often thought of it as a sort of indicator of just how much people want short, clear, egoless descriptions of ways of working that have power to make things better.I never understood Marc's title for this article, so I asked him to explain it:

What would I change about it today? Hmmm.... Remember that it was written before the web. About '93 or so, I think. At the time, the new news in that column wasn't just using paper to make prototypes, it was the idea of prototyping at all. Of course people had been making prototypes since forever, but in the software world, it wasn't *really* happening very often. When it did, the prototype itself was usually an expensive piece of code.

So the industry was having a conversation about a shift from waterfall processes, from 'first specify, then build,' to a recognition that iteration is *necessary* for discovering the specifications. That you can NOT write complete specs without using attempts-to-build as a way to better understand both the problem and the solution, and the faster you do this the better. Damn cheeky claims back then.

I don't think that conversation is over, by the way. I think design and construction are still typically too separated. And our tools make it difficult to continue design into the construction effort. Once you see and experience the software or product, once you see it in use, you can usually see how to improve it. People are slapping themselves on the forehead in usability observation rooms around the world. 'Why didn't we see that before?!'

When you make paper prototypes, design and construction are mingled in a lovely useful way. And it's an activity that easily affords collaboration. Still the two strong points in its favor, IMHO."

"Why 'tiny fingers?' You know, I thought a lot more people would understand that reference. Maybe it says something about my childhood. To me, 'tiny fingers' is a cultural reference to books about "adult" topics made accessible for children. And if "tiny fingers" is in the title, chances are you're going to be doing some kind of activity. You're going to get out the scissors and paste. I thought I was writing a title that packaged two things that usually don't go together: a 'serious' topic like prototyping, and an invitation to playful craft as a way of working. Plus I can't bring myself to make titles (or even articles) that take themselves too seriously. There's way too much over-inflation in our literature, and remember this was CACM. I wish I could have called it, 'None of us really know what we are doing.'But, surely no one is doing much paper prototyping any longer, right? Not according to Nathan Moody and Darren David of Stimulant who design cutting edge, multi-touch natural user interfaces. At their IxDA-SF presentation last month ("Multi-Everything: Multi-touch and the NUI Paradigm"), both claimed they paper prototype extensively and have never found anyone who can iterate faster digitally.

I asked amazon and google about this, and see it's still happening a little:Okay, I made up that last one."

- Easy puzzles for tiny fingers

- Kitten on the keys: Descriptive solo for tiny fingers (!)

- Dude, you have tiny fingers

Marc "tipped his hat" to Bill Buxton, who wrote the fabulous and recently-published book, "Sketching User Experiences: getting the design right and the right design." However, Bill distinguishes between sketches and prototypes, arguing that they serve different purposes and are used most at different stages of the design process -- the former for ideation, the latter for increasing usability. Regardless, paper is among the tools he advocates for both.

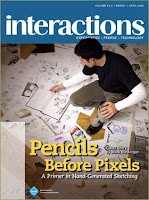

I encourage you to also take a look at Mark Baskinger's excellent cover story in the March+April 2008 issue of interactions magazine. The title: "Pencils Before Pixels: A Primer in Hand-Generated Sketching." You can download Mark's worksheets from the interactions magazine website.

I encourage you to also take a look at Mark Baskinger's excellent cover story in the March+April 2008 issue of interactions magazine. The title: "Pencils Before Pixels: A Primer in Hand-Generated Sketching." You can download Mark's worksheets from the interactions magazine website.And other lo-fi techniques have received recent attention, including Brandon Shauer's sketchboards for exploring and evaluating interaction concepts quickly.

Over the years, lo-fi prototyping has had more than its share of detractors. But, clearly, it lives on -- as it should.

However, it looks like it is going to be very hard to get rid of any of those boxes in my basement.

___

Years ago, Marc Rettig served as Features Editor for interactions magazine, though he tells me the opportunity he was given to play that role was less than minimal. Jon Kolko and I are giving him another opportunity, as we have recently added Marc and others to our team of contributing editors. More info on those additions and other changes will appear in interactions magazine and on the interactions website.