A version of this post has been published on Medium.

Prologue

I’ve interviewed

lots of people on stage at professional events over the years, engaging in and

facilitating conversations that are often wide-ranging though with a primary

focus on design. And when Jon Kolko and I were Editors-in-Chief of interactions magazine, we ended most issues with a simulated “cafe” conversation on topics of relevance to that issue’s content. We started to resurrect such

conversations last year on topics of relevance to design today (see "On the relationship between design and activism" and "On the importance of theory to design practitioners"),

and I’ve started having such conversations with others as well (see "On what it takes to effectively design the future of healthcare"). Here is

the second with another: a conversation with Marc Rettig.

Marc is a

Principal at Fit Associates, a firm based in Pittsburgh, PA that helps people

learn to create change together; he also teaches at CMU and SVA DSI. I met Marc many years ago when he was Chief

Experience Officer at a Chicago-based design firm called HannaHodge. (Marc,

always a trail blazer, was the first Chief Experience Officer anywhere ever.)

In April, I interviewed Marc when he met with my students remotely during a

course I was teaching at the Austin Center for Design. I invited Marc to extend

that conversation.

---

Posing the big question, and seeing companies as emergent patterns of relationship

Richard: I’ve been exploring what it takes for companies to become (more)

“ethical” — to pursue goals that are, for example, social or environmental as

vigorously as goals that are economic — to move beyond side Corporate Social

Responsibility initiatives that many claim exist mostly for PR reasons or to

make employees happier about working there. Jon Kolko and I addressed this a

bit in our conversation on the relationship between design and activism,

and you began to address it in February via a Twitter conversation you had with Jared Spool.

Do you have the

answer? Do you know what it takes for companies to (begin to) make it (more of)

their responsibility to improve society or the environment?

Gardening versus changing

Marc: Hoo boy, there’s a lot in there.

I’m not saying

this is what you asked for, but a question like that can seem to expect a

direct, action-oriented answer: “The Thurston-McKinney approach will set you on

the right path for sure.”

But of course

it’s messier than that. There ARE some good ways to get started, and good tools

we can bring to bear. But that beginning and those tools are systemic rather

than direct.

So I need to

start with a way of seeing organizations and change that’s different than the

view we all seem to have soaked up through the Big Old Societal Story.

A company is an

emergent system made of people in loose relationship, not a machine made of

parts in tightly constrained order. We can’t “work on it” with predictable

results.

It is more

accurate and useful to see an organization as a process. And to notice that

this process (or really this woven bundle of patterns of processes) is mostly concerned

with reinforcing its existing structures and repeating its old processes and

stories. That process view of organizations gives us…

--Useful question #1--

How can we

nurture the conditions in which at least some part of the organization pauses

its process of repetition and reinforcement of the old story, so it can begin

exploring a new story?

As some systems

sage has pointed out, “No gardener ever made a rose.” But good gardeners are

great at working with the conditions in which roses can become healthy and flourishing. That is a clue.

Relationships as our "material"

I’ll make one

more point about social systems, then I’ll pause.

Say you’re

setting out to influence or change an organization to “take responsibility to

improve society and the environment.” The most common thing has been to focus

on the people—the executives and managers maybe, or the strategic innovation

group. The naïve idea is to somehow persuade or motivate them to care, to take new

actions, to measure success by different values. This kind of persuasion has

been tried so many times in so many ways, we can say confidently that

persuasion is a dull tool.

If people are the

“material” of our approach to change, then we’ve got two problems. One is that we’re

working with the least malleable aspect of the system. All the models of

individual change tell us that it takes time, it’s not easy, and it doesn’t happen

because someone else wants it to.

The other problem

is that we’re trying to apply a parts-and-whole view of a system, when social

systems are mostly made of relationships. It’s easy to see the outcomes we’d

like to change as coming from the people in the organization. But that’s not

what’s really going on. The outcomes emerge

from the relationships between those people, and from thousands and thousands

of conversations across those relationships. For the topic we’re discussing,

there’s barely even such a thing as an individual person.

When we focus on

relationships as our “material,” we see people as participants. We become

interested in the conversations through which those relationships are formed

and maintained or blocked and disrupted. We notice how a large proportion of

those conversations have to do with maintaining and repeating the status quo.

“Johnson, I know you’re new here and full of ideas, but why can’t you be more

like Williams? He was innovator of the year!”

Conversations

shape relationships, relationships play a dominant role in individual change

and development, and conversations are far more malleable than individual human

behavior. So if people are not the “material” of change, but instead we’re

focused on patterns of conversation and relationship, we have,

--Useful question #2--

How can we work with conversation and relationship in ways that can attract and sustain new patterns of organizational behavior?

How can we work with conversation and relationship in ways that can attract and sustain new patterns of organizational behavior?

Organizational narratives, the seeds of change, and four ways to "cross the gap"

Richard: Great questions, both prompting additional questions.

Regarding the

first… I don’t want to over-extend the metaphor, but don’t good gardeners ever

plant the seeds in addition to working the conditions in which the roses become

healthy and flourish? Or, within an organization, is it better to find the

desirable seeds that have already been planted or just assume they are there

somewhere? If one of the latter, how does one gain access to nurture their

growth (or must all change occur from within)?

And both of your

questions bring to mind John Hagel’s concept of a “narrative” which, unlike a “story” which, as defined by Hagel, has a beginning, middle,

and end, is open-ended, inviting participation and contribution to shape how it

unfolds. According to Hagel’s definition, a corporate narrative is about the

corporation’s audience rather than about itself. Nevertheless, how can a

narrative about the goals and roles of a company become a part of the

conversations its people have and, hence, the relationships those conversations

help shape? And how can such conversations and new relationships be nurtured?

However, isn’t

the approval of people still needed? Don’t people still need to be convinced at

some point or at multiple points that change — even change in the form of

different conversations — is beneficial? While facilitating the exploration of

a new corporate story via nurturing new conversations is important, people

still need to be persuaded.

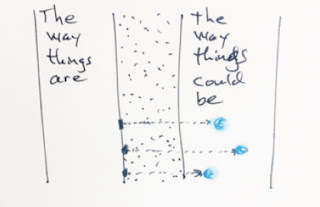

Marc: I like your question about where

the seeds come from. Sometimes I use a little drawing to talk about that

question. On the left side is “the way things are,” on the right is “the way

things could be” or the way we’d like them to be, or sense that it is possible

to be. And in between is a gap.

Somebody, it might be Brené Brown, calls that “the

cynicism gap.” It’s the gap we aren’t sure how to cross, and with enough

repeated disappointment we might start to believe it can never be crossed.

Water the sprouts that already exist

So how do we work? How do we go about getting ourselves

across the gap together? One answer is to look for the seeds that already

exist. John Thackara sometimes says, “What needs to

happen is already happening.” By which he means, whatever big challenge or

stuck situation you’re considering, you’re almost certainly not the only one.

Others have already started, some have made progress, and a couple of them are

probably onto something.

Then he says, “You just need to find where it’s

happening, connect those people to each other, and ask them what they need to

grow.” And he’s more or less made a career out of that statement.

Plant new seeds

So that’s the approach of “The seeds have already been

planted.” And you’re right, there’s also the “Let’s plant some seeds ourselves”

approach. We can manage a portfolio of little pop-up futures—experiments to

find out what will attract people toward new patterns of behavior and

relationship. I draw them like this, like they’re able to latch on to the edge

of the gap and pull it closed.

These aren’t prototypes in the way the business and

design world usually thinks of them. They are experiences of a possible way of

living, working, relating, etc. For example, “You’ve said your two departments

don’t get along and seldom talk. Each of you send a vertical cross-section of

your people, and for one week you’ll try three different kinds of collaboration

and communication. At the end of the week you’ll design a set of

inter-department experiments—artifacts, roles, rituals, practices, processes,

etc.—that a) you have reason to believe might work, b) you can establish as

practice if they’re great, and c) you can stop if they’re not great without

causing any damage.

This is an

oversimplified version of Dave Snowden’s approach to managing in complexity,

and it has great power. There are many less principled grassroots versions of

this out there, some of them pretty inspiring. Take a look at Better Block (TEDx talk & website) for example.

There are at least two other overall strategies for

crossing the gap. I’ll say less about them, but just to complete the list, one

is to build creative capacity in the community so more seeds will sprout on

this side of the gap. Another is to convene across the system and make a

facilitated journey of co-creation together. These all have different expressions

in different fields, but so far as I’ve been able to find those are four ways

people are successfully going about crossing the gap.

Both of those “seed” approaches—planting seeds and nurturing

the sprouts you find—are grounded in good theory about how socially complex

systems change. You don’t shift the dominant paradigm through direct pressure

on its center. You don’t persuade those who are fully invested in the old

pattern, convincing them to change their minds and adopt a new one. Instead of

persuading, you attract to something. You activate urges that are already present.

Some people call the experiments and sprouts “hopeful monsters.” To people in the comfortable middle

of the system, they’re strange. They look like monsters. But to others they are

hopeful, they are attractive. As they become more visible, as they connect,

they become more and more ready to move to the center once it inevitably

weakens.

Persuasion vs. attraction and the stories that keep us stuck

That point about attraction versus persuasion connects to

your question about narrative. Narrative or story is a hugely important topic.

In our work with facilitation (“hosting conversations that matter”), we are

sometimes very deliberate in working with the kind of deep narrative you

describe.

I mentioned people who are fully invested in the old

pattern. They repeat and reinforce its behaviors and relationships. “Johnson,

you’re doing it wrong. Why can’t you be more like Williams?” What’s under that?

Where does it come from? It comes from that underlying narrative about the

company, its place in the world, and their place in it. It might be

unconscious. But it is repeated constantly in the choices of who to reward, who

to mock, what to prioritize, what to fight for and against.

“We sell as much coffee as we possibly can.”

“We provide the comforts of home and office, with

coffee.”

“We are partners with the planet and society in the use

of coffee.”

The old story is comfortable. We’ve been living it a long

time, we know how to do it, we know our role. But we have to stop the old story

in order to find the new one. It’s uncomfortable—a real stretch!—to hit pause

on the story that defines your identity and your place in it all, and move into

a place between stories—a place that makes room for uncertainty, that gives

time to find the new story that has the strength to draw you out into new

patterns.

You asked how this kind of conversation can be nurtured. And

you asked if it isn’t always the case that some people need to be persuaded to

change, to explore, to let go of the old story and consider a new one.

Can you persuade

someone to have an open mind? I find persuasion to be the dullest knife in the

drawer, but for reasons I don’t understand it’s the one people always seem to

reach for.

If you like I can expand and give examples, but the big picture

answer is to say, 1) experiences have far more power to open minds than any

argument, and 2) there is a very old craft of hosting conversations in

ways that make it more likely that people will suspend their presuppositions,

see through other people’s eyes, reflect and reframe together. And we can

connect those experiences over time with some real hope of shifting things.

Earlier in this conversation I mentioned that it’s useful

to view a company as a process, busily repeating its patterns or perhaps

experimenting with new ones. Exactly the same can be said of people. Of

leaders, decision-makers, designers, builders. They are in the process of

repeating their old stories, and/or becoming the next version of themselves.

The gardener suggests tending to the conditions for their becoming, rather than

trying to persuade them to stop being who they are.

What does that look like?

Richard: Suspending presuppositions, seeing through

other people’s eyes, reflecting and reframing with others, … — all skills

purportedly in the designers’ wheelhouse, and while perhaps those experiments

with other ways of doing things aren’t prototypes in the way the design world

usually thinks of prototypes, it seems like designers are at least somewhat

well-equipped (and are well-positioned to become better equipped) to play a key

role in making or helping to make all of this happen. But how might they be

empowered to do so? Via experiments with such empowerment?

Plus, since we’re

discussing all this in the context of exploring what it takes for companies to

(begin to) make it their responsibility to improve society or the environment,

what might little experiments in that

direction look like?

The indiscernible beginnings of a storm of change

Marc: Maybe it will help to try to make up a story – a bit of process

fiction. The story is needed because my response to the two things you just

asked about--the prototypes and the role of designers--need the context of a

bigger story.

How does the

story get started? What is the beginning of an organizational shift toward

social and environmental responsibility? In her book, The Storm of Creativity, Kyna Lesky wonderfully compares creativity

to a thunderstorm. When does a storm begin? What is the sequence that leads to

the formation of the right clouds, the right conditions? What reinforces those

conditions until the rain begins to fall? We can’t say, because it is not a

matter of direct cause and effect. It is a matter of pattern emergence in

complexity.

So in our

imaginary organization let’s say there are the seeds of a storm. There are

people who feel uneasy with the status quo. A few managers have been to the

Sustainable Brands conference. HR has hired a diversity and inclusion manager,

and emails are circulating about other companies’ local community efforts. This

is the visible, surface evidence – the smoke. The fire producing that smoke is

still invisible in the quarterly reports and project briefs. It’s still in the

form of coals, deep in people’s thoughts and emotions. Managers who find

themselves daydreaming on the drive home, wondering about moving to a company

where they can feel like they’re giving something to the world other than more

disposable containers.

It starts with listening

Should we make

this story about a lone catalyst? A team leader somewhere, not a VP or

anything, who decides to begin taking action? Or should we make this about

someone more senior who has a little budget and power to convene? Either way,

the first step is to listen.

What does it look

like when we listen to an organization? With a full dose of “it depends,”

listening might involve….

- Making a map of leaders and influencers, and scheduling time for deep “dialogue interviews.” More personal than business or research interviews: the story of how they got where they are, what they really care about, what they’re trying to accomplish and what’s in the way, the values that underlie their work, and whether they think about their legacy—how things will be different because of their time at the company.

- Something more systematic like a culture scan, gathering stories about the way choices are made, the way the organization is and isn’t already living out the sort of policies and behaviors we’re aspiring to. The patterns in those stories suggest where the “adjacent futures” might be—informal patterns and practices that some people are already living, moving toward, and which others feel attracted to.

- Finding the pioneers, asking what they need, and helping them connect to each other. It is often (always?) the case that when a system or paradigm is peaking, is dominant -- like the one playing out in our imaginary organization that’s driven by concerns other than long-term quality of life for all species – that’s the time when some folks become dissatisfied and start jumping off. They might not know exactly what they’re jumping toward, but they can see how things can be better, they see the damage of the status quo, and they head out to experiment. They are the seeds of the next thing. Help them find each other!

In the case

studies we’ve looked at, people take up to a year to simply listen to the

system, gather people for conversation, sense what’s going on, and put in place

the conditions for the next steps to be perceived as legitimate.

Our beliefs about change affect our default approach

Where does it go

from there? I’m working on a piece of writing that describes how our world view

– the story we’ve chosen to believe about change – strongly affects the way we

think it’s “smart” to go about working toward change.

Do you believe we

can manage our way to just, equitable, and sustainable practices through an

innovation process? Do you believe shifting the system will require a

whole-system approach? Maybe you believe in bottom-up change and the power of

the grassroots, or the power of community and dialogue across boundaries. The

importance of building capacity for participation and co-creation? The power of

place?

My point is not

that there is confusion about approach, or that change strategies are purely subjective.

My point is that organizations are complex in a truly formal sense: emergent,

nonlinear, unpredictable. And we live and work in a time of great energy toward

finding better ways to engage with that kind of social complexity. Out of that

energy comes a lot of inadequate approaches—nice tries, no cigar. There is a

lot of “I’ll just keep swinging this same hammer at these things I’ve decided

to call nails.” And there are a few really beautiful hard-working approaches we

can learn from. They all originated outside the “design” conversation. One or

two are starting to be embraced by people who call themselves designers.

What a wonderful

time to be learning and working!

Prototypes and probes: Where do they come from? What do they look like?

Well back to the

story. You asked where the prototypes come from, and what they might look like.

Where they come

from is conversations, same as anything else. And that, by the way, has been a

blind spot of design practice. We’ve spent decades on how to have good

conversations about new ideas, but little attention on the conversations before that: who needs to be involved,

who’s being left out, what’s going on, what’s possible, what gifts are

available to this situation, what great intention – bigger than ourselves and

our organization – are we aligned toward, what stories are we aiming to bring

to life in the world, how can we hold on to that intention throughout the

process, what are we afraid of, what is driving us (fear? self-interest?

creative fire?), and so on.

It’s one thing to

miss these conversations when you’re making a new blender or hospital

admittance form or whatever. It’s quite another when you’re pursuing the

question we’re talking about, which is basically about the way an organization

can be a place for soulful, life-giving creative participation of the people

who work there. This doesn’t need to feel like church. It just needs to be

open, honest, and big enough. I’m hurrying through this point because it is a

deep well and probably another conversation to have.

So maybe in our

story we get to a place where we have a gathering of people with some

commitment to shift the status quo. They have different ways of going about it,

they’re in different parts and levels of the organization, but they are joined

by a sense that a better way is both possible and deeply desired. And they’re

hip to the complexity of the situation, so they decide to work experimentally

at the edges, rather than planning some kind of frontal attack on the center of

the status quo.

The prompts might

be things like:

- “We have a few stories of socially / environmentally responsible choices and strategies in our organization. How might we get more stories like those, and fewer of the opposite stories?”

- “We have identified pockets where people are already making something happen in their corner of the organization. How might we support and amplify their efforts? How might we connect them? How can we encourage the birth of a community of practice?”

- “We know that experiences are more enlightening and persuasive than arguments and presentations. How might we engage influencers and decision-makers in experiences that invite them to re-examine their old stories and open to the idea of creating new ones?”

- “We know that this conversation is taking place in isolated silos and groups of our organization. How might we scaffold bridges of relationship and conversation between like-minded leaders, projects, and teams?”

Imagine the

experiments that might come out of such briefs! I feel funny making up

examples, because the real thing would be much more specific to the people and

organization than anything I can invent. But examples help, so maybe…

- Pop-up studios and labs: a day or a week of cross-functional exploration, or provocative experiences of possible futures

- A pecha-kucha event to help people become aware of each other’s efforts

- Learning journeys / strategic immersions: getting people out of the office to experience say: organizations that are further along in the change we seek for ourselves, the positive and negative impacts our organization has on people and places, parallel but relevant skills and contexts that can inspire our own strategies

- Any number of experimental artifacts, roles, or rituals that might make it easier for some group of people to live out their values in their work rather than setting them aside in service to status quo habits and pressures.

Sometimes the

point of the experiment is the results you hope it will yield. Much more often,

the point of the experiment is the way conversations will be born and

relatedness will increase. I wouldn’t imagine any of these ideas, even a

pecha-kucha one-off event, to be standalone. There would be attention before

and after to tend the conditions for conversation and relatedness.

If our fictional

gathering of people has the ability and sponsorship to formalize this work,

they can manage these experiments as a portfolio, learning from them all,

stabilizing or feeding the ones that spark attraction to something positive,

and dampening the ones that don’t. All the while encouraging and hosting conversations,

reflections, and new connections.

But even without

that, this sort of local experimentation and conversational fertilizer can’t

help but nurture the conditions for something new to grow. It encourages the

pioneers. It sheds light on what’s working. It is the natural starting point

for a community of practice, and once something like that has formed you are

well on the way to a new dominant paradigm. The storm has formed.

Are designers prepared for the work of social pattern-shifting?

Okay. Having said

all that, I’ll return to your question about designers’ skills: “…Suspending

presuppositions, seeing through other people’s eyes, reflecting and reframing

with others, … — all skills purportedly in the designers’ wheelhouse….”

Some barriers

I’ve taught now

in three graduate design programs, and have been a visitor to two or three

others. And I’ve spent countless hours among practicing designers and design

leaders in organizations and at conferences and so on. I’m going to throw a

blanket statement over all that, with the disclaimer that there are certainly

many hundreds of exceptions to what I’m about to say.

When I think

about all those students and professionals and managers, what qualities come to

mind besides their skills and qualities—their training, imagination, good

heart, care for craft, and so on? Here are some that come to mind for me:

- They believe that they have the tools to tackle just about anything, from beginning to end.

- They love to be recognized for their expertise.

- They’ve been soaking in the idea that the primary home for design sponsorship and the exercise of design’s power is the world of business. Which is to say, most designers think in terms of business goals and intentions.

- They’re so used to working with technology that they tend to assume (often unconsciously) that it will somehow be part of the “solution” they design.

- They believe that the best way to work is in strong small teams. Outside the team they see stakeholders and “users.” Their idea of participatory work is an afternoon workshop with stakeholders and users.

- They’re in a big hurry. Grad school, internships, first jobs, agencies, big companies, non-profits,… all their experience has been intense, aggressive, non-stop. They don’t like that this compromises what they know to be good practice: taking time to really immerse and understand, to explore many directions, giving equal time to divergence and convergence, not rushing to conclusions, evaluating alternatives, and so on. They don’t like it, but they don’t know how to fight against it. And in fact many take pride in the fact that they can get to results quickly.

- They aren’t in the habit of stepping back to see the connection between their current project and the long-term greater good, and when they do they are poorly equipped to stand on its behalf.

All of these make for terrible

conditions in which to work in the way I’m suggesting is necessary for

fostering social shifts: “suspend presuppositions, see through other people’s

eyes, reflect and reframe with others.”

You are right

that these that these are all close to the heart of design. We could go deeply

into each of those things, but I’ll pick just one to harp on: “with others.”

The critical piece: "Together" -- participatory emergence

What most

designers aren’t trained to do, and what most processes don’t include, is

helping everyone who is somehow a stakeholder in the situation create together.

Yes, designers seem to be well-positioned to become equipped for a truly participatory, systemic, and emergent way of working. In my classroom experiences the biggest challenge for designers is to let go of their engrained sense of themselves as expert problem-solvers who will be the source of the good ideas and the shapers of the resulting forms.

Yes, designers seem to be well-positioned to become equipped for a truly participatory, systemic, and emergent way of working. In my classroom experiences the biggest challenge for designers is to let go of their engrained sense of themselves as expert problem-solvers who will be the source of the good ideas and the shapers of the resulting forms.

Design practice

is full of hero mentality. It is still colonial, in the sense of “I’m here with

knowledge and skills to make things better for you, people who aren’t like me.”

Design doesn’t trust the people it calls “users” to be full peers in

co-creation.

When it comes to

the social complexity of organizational culture, no single project will suffice. No single design is sufficient. The

challenge will not yield to research and expertise. You cannot

design-and-implement, you can only bring your gifts to your participation in

the process, your citizenship in the future.

There is plenty

of design-and-implement work to do down in the details, and huge help to be

given in service to insight, communication, facilitation, and so on. But

there’s so much work to be done together before

we know what to design. Designers can make themselves ready for that work by

- expanding their ability to work in complexity and uncertainty,

- learning to bring their process expertise into communities of peer co-creators,

- learning to focus more on the conditions from which new patterns of relationship and behavior arise—the conditions in which a storm might form—rather than “solutions to problems.”

It starts with ourselves, and experience trumps persuasion

Richard: I agree with your assessment of the tendencies of today’s designers, design students, and managers and of their readiness (or lack thereof) to work in the ways that you argue are crucial. What you argue is consistent, I think, with what I’ve argued needs to change in a lot of design education and even in the way design is framed, and there are a few frameworks for engaging in design in ways related to this, including equity-centered community design and transition design, the latter with which you are probably intimately familiar since its development has been led by some of your colleagues at CMU. I’m encouraged by the increased attention such proposed changes are receiving.

Regarding the

relative power of experiences versus persuasion to open minds, a past tweet by

Dave Gray seems relevant:

Years ago, I spearheaded a project in

which I sent a diverse set of stakeholders — many strongly committed to very

different perspectives of how potential customers of a proposed business

behaved and what they would want— out into people’s homes and workplaces to

find out. Those experiences opened minds dramatically, subsequent workshops and

conversation resolved most remaining differences of opinion, and the

stakeholders asked that all future projects be run in a similar fashion.

However, one individual — the executive leader of the project — did not engage

in those experiences, and the course of the project (i.e., the nature of the

business offering), though signifcantly affected, wasn’t changed as

dramatically as many argued was advisable.

That story is

akin to a story you shared recently in comic strip form,

which concluded with comments of concern. OK, this is a tad weird, but I’m

going to quote you here:

“The biggest difficulty in this work came from

lack of executive involvement. The team had an experience that transformed how

they saw the company’s place in the world, and which led them to a new kind of

strategic direction.

But then the team found itself having to

persuasively communicate unconventional ideas to executives who hadn’t been

through the same experience. They had remained in the same institutional

structure and old everyday conversation, while the team had been shaken into a

new realization by their travels, new friendships, and serious reflection.”

So, it seems that

one cannot always avoid the need to (attempt to) persuade.

Lastly, the act

of gardening takes time, sometimes lots of time, as you have stated. But we are

already experiencing multiple significant social and environmental crises. Do

we have the time that such gardening requires?

Business as usual: unredeemable?

Marc: Oh, I’m glad you

mentioned “significant social and environmental crises.” I read your conversation

with John Kolko in which you made a half-joke about not pontificating. But two

weeks ago I promised a room full of people that I would start speaking up more

often about a couple of things, and given the topic we’re discussing this seems

like just the right time to do so.

There are a few

important topics that we too seldom talk about in design, and unless we get

brave, stop avoiding them, get humble, and begin the long walk into their wide

territory, we are going to continue to do more harm than good.

Two pillars of our dysfunctional status quo

We stand on and

work in a long history of systems that leave people out, that deliberately give

some people advantage at the cost of other people’s disadvantage and suffering.

In the U.S., that dynamic has been predominately based on race. It’s getting

easier all the time to take ourselves to school on this topic. We don’t talk

about it nearly enough. How must our practices change in order to contribute to

an equitable and just society? Can we start experimenting, making commitments,

and telling each other stories about these changes?

We stand on and

work in a long history of systems built on an assumption of growth as the

measure of success, as the engine of business, as an undiscussed given. Growth

in what? Quality of life? Wellness? Peace? No, growth in one thing. Profit. We

say we practice “human-centered design,” but the fundamental metrics of our

business sponsors and the systems that support them will refuse to put humans

at the center unless they believe it will create more profit.

And as Joanna

Macy says, any third-grader can see that growth has limits in a world of

limited resources. But if you say that in a boardroom they think you’re being

silly.

A story big enough for a lifetime

So we shouldn’t

end this conversation about our hypothetical company without getting seriously

big-picture for a moment. I want to make sure I don’t give the impression that

I believe that with the right new approach and methods, it’s otherwise business

as usual. We have been talking about organizational responsibility and change

at the scale of one organization and an effort of a few years. But let’s not

kid ourselves. This is not a one-project, learn-a-few-new-tricks kind of

conversation.

This is a paradigm

question. It reaches deep below the emotional layer, down into the place of

identity, care, and sense of connection. Millions of managers have built their

entire career on the assumptions that these questions invite us to challenge.

That’s scary, that’s disorienting, and it causes many people to get defensive,

to grip tightly to the story in which they’ve finally come to be comfortable,

to feel known and accepted, to feel capable. The dominant paradigm comes with a

library of how-to books. The next paradigm, the one yet to be born, can

currently offer only a few clues amongst uncertainty.

In light of this,

persuasion is a ridiculously inadequate tool. It’s pea-shooter versus glacier. The

move to whatever a sustainable and equitable society will not be a tidy process

of reason and debate. It will be (and already is) a messy, billion-fingered,

organic, emergent process of co-creation. It will involve creating attractive

alternatives that draw people forward much more than it involves “changing” the

participants in the current paradigm to somehow act differently together. In

the process, I expect that most of the institutions and systems in the center

of the current paradigm will come to an end.

Some say this

great transition, this “Great Turning” compares in scale of impact to only

two previous shifts: the agricultural era and the industrial age: each involved

creation of new alternatives, displacement or destruction of old patterns, and

a shift in societal consciousness.

Now THAT is a

story big enough to live into. Unlike all the previous invitations I have

received in my career—to improve home appliances or a web site, to bridge

division between departments, and so on and on—unlike all of those, I find THIS

invitation too thrilling to refuse.

. . . .

Richard: Thank you for the conversation. You knock me out, Marc. I look

forward to many more conversations.

Marc: That’s kind of you to say. Thank you very much for a fun

conversation, and yes I’m sure there will be more.