“My company is examining where in the organization chart the UE team belongs. We are a $1b enterprise software company and the UE team is 12 people and two years old. We started in Engineering, were moved to a staff shared services organization, and recently were moved into Product Management in order to have a greater, more strategic impact. Our role is primarily to work with Program Managers, in Engineering, to write product specs.John is just one of many people in a wide variety of companies who have been trying to answer some variation of this kind of question.

Some are suggesting that UE belongs in Engineering, primarily because 'product management should not be writing specs' and 'no other companies have UE in product management'. Only a small 'strategic' UE group would stay in PdM, doing research and standards but no direct specification.

As UE Director, I’m comfortable in PdM. I think we (in PdM, representing product appropriateness, competitiveness, quality) can partner with PgMs (in Engineering, representing efficiency, feasability, schedule, constraints) to leverage each other’s skills to reach a good spec. I worry that being in Engineering will compromise the UE design towards the needs of engineering.

(Where does UE belong?)”

Earlier this year, I co-taught a Managing User Experience Groups course via University of California Extension in the Silicon Valley. And one of the many issues we addressed during this course was "where should User Experience groups be positioned?" The positioning of User Experience was considered to be very important to those who took course, many of whom were User Experience group managers. It has certainly been of importance to me when I've managed User Experience groups. And it was considered very important to the many User Experience Managers, Directors, and VPs we interviewed when we were preparing the course.

So, where should "User Experience" be positioned in a company?

The best answer to that question might depend on what "user experience" means in the company. Thus far in this blog entry, "User Experience" has largely been a reference to a group of people that in some way attends to "user experience." But, what is the scope of what the User Experience group attends to?

Without question, the term "user experience" means different things to different people. For example, here is a definition published by Dirk Knemeyer in Dirk's blog about a year ago:

"…user experience is specifically native to digital interactions. That is what defines it: having to do with the holistic quality of digital interactions. …what characterizes user experience, what sets its boundaries as just one component of human experiences, is the fact that it has developed from and is centrally a measure of the digital."Here is a bit of a broader definition from Don Norman, the person who purportedly coined the term "user experience" several years ago. This is how Don defined the term one of the times I interviewed him on stage (download the full interview, PDF 1.8MB):

"I believe that what's really important to the people who use our products is much more than whether I can use something, whether I can actually click on the right icon, whether I can call up the right command... What's important is the entire experience, from when I first hear about the product to purchasing it, to opening the box, to getting it running, to getting service, to maintaining it, to upgrading it. Everything matters: industrial design, graphics design, instructional design, all the usability, the behavioral design... so, I coined the term 'user experience' some time ago to try to capture all these aspects."And here is an even broader definition, published in the blog of Peter Merholz about a year ago:

"User experience should not be just about interactive systems -- it's a quality that reflects the sum total of a person's experiences with any product, service, organization. When I walk into a store, I'm having a 'user experience.' When I call an airline to make a reservation, I'm having a 'user experience.' And innumerable elements contribute to affect that quality of experience."Should the breadth of the definition of the term impact the positioning of "User Experience" in a company?

What does "user experience" mean where you work? Some companies use the term "user experience," when all it really means in that company is "user interface." Some companies use the term "customer experience" instead, which almost guarantees a certain positioning. (See "Is 'user' the best word?" for more about the impact of such word choices.)

What definition of "user experience" would be of greatest benefit where you work?

Something else to consider is how the positioning will affect working relationships. During the CHI 2005 plenary address, Randy Pausch argued that "neither side can be there 'in service of' the other." Don Norman elaborated on this in the interview referenced above:

"An extreme oversimplification that a friend of mine made is that there are two kinds of people in organizations -- there are peers, and there are resources. Resources are like usability consultants -- we go out, and we hire them. We’ll hire a consultant, or we’ll have a little section that does usability and think of it as a service organization. We call upon them when we need them to do their thing, and then we go off and do the important stuff. That’s very different than peers, where a peer is somebody I talk to and discuss my problems with, and who helps to decide upon the course of action."(For more on this, see "Getting the organizational relationships right.")

In the discussion list posting quoted at the start of this blog entry, John Armitage expressed concern about the impact on working relationships of being positioned in Engineering. And he said more (again, quoted with his permission) in a follow-up posting:

“The big question is authority. Engineering is happy to have all the advice they can get, as long as they maintain control over what gets built. My goal is to give my designers the ability to escalate detailed UE issues outside of engineering so that they can be heard and discussed by Product Mgt. If UE reports to engineering this can be prevented.”But similar things can be said about being positioned elsewhere. For example, the VP of Customer Experience Research & Design at a Fortune 100 company told us about his discomfort with being positioned within Marketing, as paraphrased below:

"There should be a natural tension between Customer Experience (pulling to pure experience, facilitating completion of tasks, etc.) and Marketing (which is about selling and profitability and driving traffic etc.). Since we are positioned in Marketing, we share Marketing's goals, which can be challenging, since Marketing might go for short term gain, which results in long term loss."Should User Experience stand alone? If standing alone, User Experience can still risk being treated as a resource. But, the above-referenced VP of Customer Experience Research & Design thinks his group should stand alone. And in some companies, it does stand alone.

But for User Experience to stand-alone and not be treated as an optional resource, some have argued that you need a seat at the C-level executive table (see arguments of this nature in "The Chief Experience Officer" and in "Making changes to a company's culture").

A year and a half ago on stage at Stanford University, I asked Don Norman about some of these issues, and here is part of what he said:

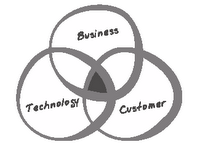

"I thought that the product teams at Apple when I was there were very effective. ... Any given product team always had somebody from marketing, always had somebody from the user experience group, always had people from the engineering groups. And there was communication with sales. And in that working group where you had at least these three different (groups represented) -- there was a user experience requirements document, and a marketing requirements document, and an engineering requirements document -- I thought these teams worked really well together. So well that people would forget which part of the team they were, but they were all solving problems."

Don's words are reflected in the diagram at left which he published in his 1998 book, "The Invisible Computer."

Don's words are reflected in the diagram at left which he published in his 1998 book, "The Invisible Computer."Similar diagrams have been published by others, including Scott Berkun in 2005 (see "The magical interdisciplinary view" and below right).

So, should User Experience never be positioned within Marketing or Engineering?

Perhaps the best positioning depends on the nature of the company and might change over time. For example, in another blog entry, I commented on the importance of "partnering with power." In some companies, perhaps the best positioning is in the organization with the most power.

Perhaps the best positioning depends on the nature of the company and might change over time. For example, in another blog entry, I commented on the importance of "partnering with power." In some companies, perhaps the best positioning is in the organization with the most power.However, what is the ideal positioning to work toward?

In that interview of Don Norman a year and a half ago, I asked Don, "In a business, which organization should own the user experience?" In a blog entry I authored shortly after that event, I reported that Don's answer was pretty much "All of them." Here is more of what he said:

"Why should any particular organization own it? The company should own it. ... Who owns user experience at Apple? In part it is Steve Jobs, but in many ways it is the company. Yes, it was Steve Jobs who put in the focus and said 'do it this way, or go away.' But I think a successful company is one where everybody owns the same mission. Out of necessity, we divide ourselves up into discipline groups. But the goal when you are actually doing the work is to somehow forget what discipline group you are in and come together. So in that sense, nobody should own user experience; everybody should own it."(For more on the issue of organizational positioning and user experience ownership, see "Walls.")