Brenda Laurel, a highly-respected designer, researcher, writer, and currently chair of the Graduate Program in Design at California College of the Arts, had surgery last fall at the Stanford Medical Center. Brenda tweets infrequently, but here is what she tweeted following the surgery:

If you've read my "nightmare" blog, you know that Brenda's tweet would pale in comparison to the tweets I would author about my patient experience.

Were our experiences unusual? Sadly, no. After spending two days in the hospital last year with his young daughter who was undergoing some diagnostic tests, Alder Yarrow, a former colleague of mine, recounted his experience and concluded:

"Of all the industries we interact with regularly as consumers, the medical industry definitely defines the low point in quality and consistency of customer experience. Most of us emerge from interactions with the medical establishment feeling more like victims than paying customers."

Speaking of this lack of patient experience consistency, Dave deBronkart, a.k.a. e-Patient Dave (a full-time, empowered patient advocate), detailed "physicians' unwarranted variation in practice" which "has been shown to cause immense unnecessary surgery, with the resulting costs and inevitable percentage of errors and deaths after surgery that wasn't necessary in the first place."

Unnecessary deaths were addressed in a U.K. researcher's tweet in December:

According to leadership guru Steve Denning, "medical errors cause in the order of 100,000 deaths per year."

In a commencement address at Harvard Medical School last year, Atul Gawande M.D. said:

"Two million patients pick up infections in American hospitals, most because someone didn't follow basic antiseptic precautions. Forty per cent of coronary-disease patients and sixty per cent of asthma patients receive incomplete or inappropriate care. And half of major surgical complications are avoidable with existing knowledge."

A recent study by the Department of Health & Human Services revealed that:

"One in four hospital patients are harmed by medical errors and infections, which translates to about 9 million people (in the U.S.) each year. ... Hospitals are doing a poor job of tracking preventable infections and medical errors and making the changes necessary to keep patients safe."

The author added, "...hospitals don't seem to give a damn about fixing things."

Jay Parkinson M.D., viewed as a rebel in the medical community, wrote about the experience of getting his dog properly diagnosed and treated when his dog was on death's door. He contrasted that experience, which he raved about, with the experience that most humans receive in the U.S.:

"the dominant experience for most people...is unsafe and inhumane."

Donald Berwick M.D., who oversaw Medicare and Medicaid until this past December,went further:

"Health care is broken. ... We have set up a delivery system that is fragmented, unsafe, not patient-centered, full of waste, and unreliable. Despite the best efforts of the workforce, we built it wrong. It isn't built for modern times."

My patient experience was plagued from the get-go by a major misdiagnosis. So-called rare diseases -- diseases, including mine, that have been diagnosed in fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. -- often take a long time to diagnose: greater than 5 years in many cases, according to the National Institutes of Health's Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR). Almost two decades were required to correctly diagnose the rare disease of a nurse I've met online who now devotes a lot of her time to educating the public about her particular disease which caused her to suffer multiple brain aneurysms.

Delayed and inaccurate diagnoses are two of several problems that tend to plague all victims of rare diseases. According to the Presdient & CEO of the National Office of Rare Disorders (NORD), other problems include difficulty finding an appropriate medical expert, few treatment options, lack of awareness and understanding of the patient's needs, and a sense of isolation. All of these were among the problems I experienced and to some extent continue to experience.

Should anyone ever need to experience those kinds of problems? My answer is, "no." Nor should anyone with any disease have to experience a healthcare system that is as broken as ours. The patient experience in the U.S. (and in many other countries) needs to be transformed. Not just improved, but transformed, as reflected in this graph from Kerry Bodine of Forrester Research. And fast -- as fast as possible.

What all contributes to such poor patient experiences?

Here is a subset of the contributors -- some of the systemic contributors, some of which overlap with others, and all of which contributed to my terrible patient experience.

Doctor arrogance

This contributor has been receiving a lot of attention in recent months. An article in The New York TImes last year started with these words:

"Doctors save lives, but they can sometimes be insufferable know-it-alls who bully nurses and do not listen to patients."

Jay Parkinson M.D. weighs in a lot on the topic of doctors being "insufferable know-it-alls." For example:

"Doctors have such a preoccupation with being right, they can't tolerate being wrong."

And the title of a report published a couple of days ago by the LA Times alone says a great deal: "Many doctors hide the truth about medical errors, study finds."

Because nurses are bullied so often by doctors, nurses more often than not do not have the courage to speak up when doctors make errors. A recent occurrence that got a lot attention in the press and on Twitter involved a doctor in Arizona who exploded with anger because a nurse corrected a patient's misunderstanding -- a misunderstanding caused by the doctor -- about treatment options. The doctor threatened to have the nurse fired and to have her license to practice revoked, and he successfully followed through on both threats. A report written by a nurse about this case stated the following:

"[the nurse's] story is one of an archaic medical model in which the doctor's word is supreme and we are all just nurse maids here to do their bidding. ... I'm really disgusted that a healthcare organization would bow to the tantrum of one very arrogant and immature physician. If there was one example of a surgeon with a God-Complex, this is one."

Not only are nurses afraid of doctors, so are patients. They often don't know when to talk and often fail to ask questions. According to Stanford's Abraham Verghese M.D., patients are interrupted when they do talk on an average of every 14 seconds. Verghese argues that the physical exam is a sacred ritual, one that doctors violate on almost every occasion.

Often, a patient's experience of his or her illness is critical information for an accurate diagnosis. As Paula Thornton put it in a recent discussion about patient experience in the Design Thinking LinkedIn group, "in the absence of a patient's story of the illness, you are practicing veterinary medicine."

Sadly, things don't always go well when patients insist on being heard. An example of such a case was when a doctor, in effect, fired a patient -- i.e., told her that she was no longer permitted to return -- when she asked to get a second medical opinion. It turned out that she was right to do so, as her first doctor's conclusions were wrong.

According to Stephen Wilkens M.P.H., an estimated two-thirds of physicians treat patients in a paternalistic way.

Lucien Engelen M.D., who heads an innovation center focused on the quest for participatory healthcare, put it this way:

"there is something very wrong with healthcare. At present it is mainly one-directional traffic. Doctors say that they talk to patients; perhaps so, but there isn't real negotiation with the patient. For a doctor, the patient too often is simply a disease that generated data on which they base their medical decisions. There is no real co-decision."

In a TED talk of last year, Jeff Benabio M.D. described the series of reinventions doctors underwent throughout history. Relatively recently, Jeff claimed, "we let our arrogance reinvent us ... we thought we were gods again."

USC's Dave Logan, in one of his TED talks, described the five stages that tribes -- groups of people -- go through:

- Life Sucks

- My Life Sucks

- I'm Great

- We're Great

- Life's Great

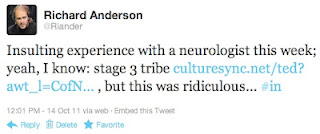

According to Dave, the problem with healthcare is that doctors are a stage 3 tribe -- people who most often talk in the terms of "I," "me," and "my." Stage 3 tribes are comprised of people who think that others should just shut up and do what they say.

Atul Gawande M.D., whom I referenced earlier, says that "We train, hire, and pay doctors to be cowboys."

In a TED talk, Dr. Brian Goldman M.D. argued that physicians live in a culture of denial, unwilling to admit to or talk about their mistakes.

"If I were to walk into a room filled with my colleagues and ask for their support right now and start to tell [stories of all the mistakes I've made], I probably wouldn't get through two of those stories before they would start to get really uncomfortable, somebody would crack a joke, they'd change the subject, and we would move on. ... That is the system that we have -- it is a complete denial of mistakes. ... [However,] errors [in medicine] are absolutely ubiquitous."

Wendy Levinson M.D. references yet another culprit in stating that "perverse incentives have contributed to physicians developing 'efficient styles' that squeeze out time to listen [to patients]..." However, perverse incentives are probably not alone responsible for this, as scores of empathy levels of young physicians correlate with patient outcomes better than any of medicine's traditional metrics.

I've tweeted very little about my patient experience, but one day I couldn't hold back:

This neurologist totally dismissed my recollection of what happened to me (to the extent that she permitted me to tell my story), claiming, for example, that the seizures that had me flopping all over the floor in a semi-consicous state must not have been seizures at all. According to her, they must have only been "muscle twitches."

As a doctor who tweets and blogs anonymously recently wrote:

"One of the worse maladies plaguing the medical field is piss-poor communication, and [my own] orthopedist has about the communication skills of a mentally-retarded clam."

A report from The Onion that weighs in on this topic is entitled, "Patient Referred to Physician Who Specializes in Giving A Shit":

"NORTH PLATTE, NE -- After visiting his primary care physician Tuesday with complaints of intense pain in his left leg, computer programmer Dan Fields was referred to a specialist who focuses on giving a shit. "I want to send you to someone who specializes in not dismissing you brusquely after three minutes," Dr. Paul Niles said as he hastily scrawled out a referral and pushed Fields to the door. "Dr. Lewis is really one of the best out there at regarding patients as actual human beings. If anyone's going to listen closely without resenting you for taking too much of his time, it's him."

Doctors do not think creatively

Jay Parkinson M.D. has written:

"Medical education and residency is pretty militaristic. You fall in line or you're out. Trust me, I've been there. If you are an 'outside the box' thinker, this doesn't last long in medical school or residency. The egos of your superiors are too threatened. This is an important fact. Doctors have such a preoccupation with being right, they can't tolerate being wrong. This is of course needed because who wants to go to a doctor known for being wrong all the time?"

And in both his TED talk and his Medicine 2.0'11 talk, Jay said:

"the medical culture is not only uncreative, it is anti-creative. ... Why should doctors be creative? ... Doctors only have pills and scalpels. ... Our reality is very different from an innovative, creative culture. ... We fall into line. ... Whenever we treat patients we treat them with algorithms. We regurgitate; we don't think creatively. We also have this thing called a god-complex... And we're just so frickin tired... And we're terrified of the law."

And they are terrified to fail board exams, as suggested by a recent news report about extensive cheating by doctors around the country taking an exam to become board certified in radiology. I mention this particular report because of the huge role radiologists played in my misdiagnosis.

As the representative of NORD tweeted during a tweetchat last summer:

According to James Howenstine M..D., "conventional medical practice in the United States largely ignores the possibility of parasitic disease" -- which is the disease that nailed me. He wrote that in 2004 but reiterated it in email to me last year. Parasitic disease is most associated with third-world countries where it isn't classified as "rare."

Doctors' dismissal of things patients learn via the internet

"You can't believe what you read on the internet," remains a common refrain among doctors -- a tribe of people who don't much care for their knowledge to be challenged. I've experienced this refrain repeatedly from multiple doctors, many making claims about my disease that my very careful research using the internet reveal to be completely false. "You simply must have not understood what you read," is the followup reaction when I present printouts of my research findings. This reaction is so common that even the few doctors who do use and know how to rely on the internet are afraid to say so:

High prevalence of medical personnel handoffs

Extending my earlier quote of Atul Gawande M.D.:

"We train, hire, and pay doctors to be cowboys. But it's pit crews people need."

However in healthcare, those pit crew members are usually separated by organizational boundaries:

"Patients experience healthcare horizontally -- with many individuals from many teams. Most breakdowns happen in the handoffs."

Some of the supportive data:

"In the past year, 42 percent of Americans reported coordination gaps related to medical records or tests, or communication failures between providers. A fourth said that their medical records or test results were not available during a scheduled visit or that tests were duplicated."

And this results in more than mistakes:

"Frequent handoffs in transitions of care, increasingly common today, make time to connect with patients even more challenging."

Other contributors exist, including difficulty finding and getting access to doctors with the needed expertise, which, as I mentioned earlier, is particularly hard for people suffering from a rare disease. And I've made only a veiled reference to the huge role played by insurance companies. However, I now turn from consideration of contributors to poor patient experiences to (potential) solutions.

What might be done to transform the patient experience given such contributors to poor patient experiences?

Here are some of the efforts that are in progress or that have been proposed.

Screening medical school applicants for people skills

Some medical schools have begun to use what is called a multiple mini interview, or M.M.I., as part of their admissions process to determine whether candidates have the social skills and the perspective needed by a good doctor. During the M.M.I. at one school, candidates are given eight minutes to discuss an ethical conundrum which they were presented with only two minutes earlier; this happens 26 times for each candidate, once for each of 26 ethical conundrums.

"Candidates who jump to improper conclusions, fail to listen or are overly opinionated fare poorly because such behavior undermines teams. Those who respond appropriately to the emotional tenor of the interviewer or ask for more information do well... because such tendencies are helpful not only with colleagues but also with patients.

Candidate scores on [the M.M.I.] have proved highly predictive of scores on medical licensing exams three to five years later that test doctors' decision-making, patient interactions and cultural competency."

At the time this article was published (July 2011), eight schools in the U.S. and 13 schools in Canada were using the M.M.I.

Teaching soft skills to medical students

Instead of or in addition to screening medical school applicants for social skills, how about training those who get into medical school? As Wendy Levinson M.D. stated in the Journal of the American Medical Association:

"medical schools and residency programs provide relatively little education about effective communication skills compared with the educational time devoted to teaching science and technology. Furthermore, medical students and residents are rarely observed during their interactions with patients or given specific feedback to improve their communication."

Here is one example of something that will be done along these lines as reported by CBS in Chicago this past October:

"A Chicago couple thinks a doctor's bedside manner is so important, they're giving the University of Chicago $42 million dollars to teach it. Matthew and Carolyn Bucksbaum are backing the Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence at the University of Chicago. It will be led by Dr. Mark Siegler -- who's been the couple's physician. They say he's the kind of doctor students should emulate. Carolyn Bucksbaum said the couple was motivated to make the donation after she once had a bad experience with an arrogant doctor who dismissed her illness."

Systems for patient rating of doctors & hospitals

Several efforts are underway beyond the use of Yelp to enable patients to rate doctors and hospitals. For example, there is a business in the U.K. called Patient Opinion which collects patient stories -- good or bad -- about experiences of U.K. health services and then passes those stories on to the right people so the stories can make a difference. Patients also have access to stories others have submitted.

There have been multiple calls for more systems of this nature (e.g., "Choosing a doctor should be like the Amazon shopping experience"). And several articles have been written arguing that patient complaints and poor ratings provide an opportunity for doctors and hospitals to improve (e.g., "Great hospitals permit patients to rip them to shreads").

Organizations devoted to achieving change

Two organizations of particular significance have been formed. One is the Society for Participatory Medicine (a.k.a. S4PM), a society that claims to be "bringing together e-patients and health care professionals," though it appears to have become mostly a voice for or of the patient community; S4PM says it is part of "a movement in which networked patients shift from being mere passengers to responsible drivers of their health, and in which providers encourage and value them as full partners."  The other organization, aimed more strongly at the medical community, is The Beryl Institute, billed as "the global community of practice and premier thought leader on improving the patient experience in healthcare." Oddly and unfortunately, neither organization appears to communicate with or know very much about the other.

The other organization, aimed more strongly at the medical community, is The Beryl Institute, billed as "the global community of practice and premier thought leader on improving the patient experience in healthcare." Oddly and unfortunately, neither organization appears to communicate with or know very much about the other.

There are a handful of other organizations with related missions, including the Center for Health Transformation, the Group Health Cooperative, and the Radboud Reshape & Innovation Center. And there are a few design consultancies focused largely if not entirely on healthcare; of these, "the future well" warrants special note, as it was co-founded by none other than Jay Parkinson, the rebel M.D. whom I've referenced above a couple of times and will reference yet again below.

Online patient communities

A major development has been an increase in the number and sophistication of online communities designed to provide support to patients and to enable patients to help each other. Notable examples include: PatientsLikeMe.com, which spans a wide range of diseases; Crohnology.com, developed by a patient with Crohn's disease; and RareDiseaseCommunities.org. Online communities have helped many to get the care they need to the point, in some cases, of saving people's lives; interestingly, one of the most publicized examples of this happened via the use of Facebook.

An article published this month in Forbes identifies and describes a few more of these online offerings. A comprehensive list is badly needed.

Convincing patients to change their ways via articles, blog postings, white papers, videos, webinars, workshops, tweetchats, talks, conferences, ... from enlightened/empowered/engaged patients

Several of the online communities just referenced provide this kind of help, along with the Society for Participatory Medicine. A large number of individuals are providing this kind of help as well.

Some of the articles and other forms of communication or interaction provide guidance for becoming e-patients; Tom Ferguson's 2007 seminal white paper entitled, "e-patients: how they can help us heal healthcare," and Fred Trotter's January 2012 blog posting entitled, "Epatients: The hacker of the healthcare world" are two examples.

e-Patient Dave's contributions, including his TED talk, are particularly well-known. Dave has recently begun to offer a series of e-Patient Boot Camps around the world. Additional patients, including myself, are also speaking out in various ways. A patient experience speakers bureau was launched just last month.

Convincing doctors to change their ways via articles, blog postings, white papers, videos, webinars, workshops, tweetchats, talks, conferences, ... from enlightened medical personnel

Doctors and other medical personnel are beginning to make contributions of this nature, some of which I've referenced above and some via the The Beryl Institute also referenced earlier. A popular blog offered by Kevin Pho M.D. features postings from a large number of medical personnel; many postings there are duplicates of postings that can be found elsewhere on the internet. Of course, since doctors aren't, on the whole, big users or fans of the internet, the reach of many of these offerings are somewhat limited.

Recent conferences of relevance include Medicine 2.0'11 held at the Stanford Medical Center, the Patient Experience: Empathy and Innovation Summit held at Cleveland Clinic, Transform 2011 held at the Mayo Clinic, and the ECRI Institute's 2011 Conference focused on Patient-Centeredness in Policy and Practice held in the offices of the U.S. Food & Drug Administration. The first three have 2012 versions upcoming. A conference that looks promising is Stanford Medicine X which will convene for the first time in September.

Some medical conferences have been criticized for failing to feature e-patient speakers or for not catering to potential e-patient attendees. A symbol was recently developed for use by conferences if patients have been adequately and appropriately considered and represented.

An interesting approach taken by NORD was the publication of an insert for a July 2011 issue of the Washington Post. NORD also sponsors an annual Rare Disease Day. However, potentially more helpful with respect to select rare diseases, including mine, was the 2011 publication of a book entitled, "Wicked Bugs: The Louse that Conquered Napoleon's Army and Other Diabolical Insects"; the author was interviewed on many television and radio programs including NPR's Fresh Air and KALW's West Coast Live. These publications, events, and programs were targeted at the public in addition to the medical community.

Employing alternative healthcare models

The most relevant change advocated is one in which healthcare becomes patient-centered. Such a model changes the role of the patient to, as referenced earlier, that of a driver rather than a passenger -- to that of someone medical personnel do things "for" rather than "to." As put by one M.D., "we need to treat our patients as people and not as disease states."

Jain and Rother have contrasted the views of patients as knights, knaves, and pawns:

"If a society conceived of patients as well-intentioned knights, it assumes that the will and values of patients should drive the structure and organization of health care... The role of policy and payment is mainly to empower patients and physicians working together toward shared aims; insurance coverage should make these interactions as facile as possible.

If a society conceives of patients as knaves, policy, management, and education efforts are designed to work against patients, not with them. Waste and even fraud are the behaviors that come most naturally to the knave -- and it is the role of physicians and health insurance companies to monitor for this behavior...

If societies conceive of patients as pawns, efforts are applied to building systems that ensure patients do what is right for themselves and for the health care system, because patients cannot be trusted to do so on their own accord.

...the patient in the United States today is seen either as a knave or a pawn and is seldom viewed as the knight. Patient-centeredness is lost in a tangle of insurance arrangements."

In spite of this dominant, negative perspective of the patient in the U.S. today, Jay Parkinson leveraged technology to develop a patient-centered practice:

"'...decades ago doctors served their neighborhoods, took cash, and didn't charge a lot because there was so little overhead. So I designed a process that went back to this model, looking at it from the patient's perspective, and just injected a little technology.'

With $1,500, he set up a house-call-only practice in his Brooklyn, New York, neighborhood, serving only two zip codes. He created a website through Applie's iWeb that featured his resume, and posted his schedule on a Google Calendar so patients could enter in an appointment time online.

He also opened a PayPal account for payments, and used Formstack to create forms for gathering patient medical histories and to create specific questionnaires for particular ailments.

Whereas most practices deal with significant costs in office management, Parkinson's start-up costs went to getting his license and buying tools, such as an otoscope and doctor's bag."

Though Parkinson's practice was solo, he used technology to consult with other experts if he needed additional insight. Indeed, a trend still in its infancy is to move medicine "from an individual to a team sport. Solo medical practices are disappearing. in their place, large health systems -- encouraged by new govenment policies -- are creating teams to provide care coordinated across disciplines. The strength of such teams often has more to do with communication that the technical competence of any one member."

The authors of The Innovator's Prescription contrasted a serial, solo approach with a team approach via the following story:

"A friend of ours has suffered from asthma for much of his life. Each specialist he saw seemed to have another possible remedy. It got to the point where he was taking multiple medications with multiple side effects, whose combined cost at one point exceeded $1,000 a month. Then he visited the National Jewish Medical and Research Center in Denver Colorado... a solution shop focused on pulmonary disease, particularly asthma... When our friend arrived, they administered a unique battery of tests, then assembled an allergist, a pulmonologist, and an ear, nose and throat specialist -- to meet together with him. They integrated their perspectives on his long medical history together with the test results, told him what was causing his symptoms, and prescribed a straightforward course of therapy that finally solved his problems."

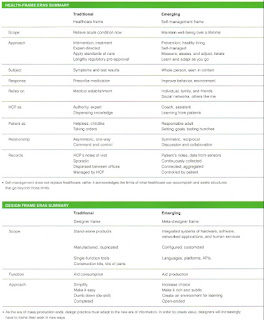

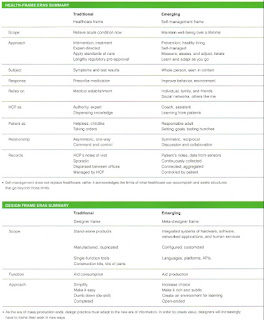

Delightfully, designers have begun to address healthcare on this level. A team of designers headed by Hugh Dubberly wrote in interactions magazine about a healthcare model of self-management that is considerably patient-centered. The nearby table -- click to enlarge -- contrasts this model with the traditional model. The section at the bottom of the table reveals how the traditional focus for the designer changes as well.

And Jay Parkinson advocates the use of design to transform:

"Going to the doctor, having routine surgery, buying bulk medications online -- all could be radically reinvented with the application of one type of medicine: designed disruptive innovation. Combining the principles of disruptive innovation with design thinking is exactly what health care in America needs. We need to disrupt the current business model of health-care delivery. And we need these disruptions to be designed experiences that are consumer-focused."

Additional models have been proposed by designers, including a model described by Matthew Diamonti, UX Director at the Mayo Clinic -- a model based on the behavior of spiders rather than the current model that is based on the behavior of bees; I'll leave it to the reader to investigate the intriguing details of that proposal further.

Other efforts are underway or have been proposed, but I consider many of them -- such as improving the design of waiting rooms and billing doctors for time patients are forced to spend sitting in them beyond appointed meeting times -- too much about "putting lipstick on the pig." One additional significant effort underway is the replacement of paper patient records with electronic records; that huge effort has been plagued with all sorts of problems due in no minor part to designs that take into consideration the behavior and needs of neither the doctor nor the patient.

I've also made no reference to the growing number of medical apps and devices that have been developed to help people monitor their bodies and their behaviors. Though such apps and devices have received an enormous amount of attention and funding, I tend to agree with Jeff Benabio M.D. who has said:

A few days ago, David Shaywitz reported that a FutureMed extravaganza put on in Silicon Valley last week was not much more than "a celebration of technology for its own sake." And Jay Parkinson, focusing on body data tracking devices, has stated:

"I personally believe that body data tracking is just hype for many reasons. The amount of money these companies are raising is way out of proportion to actual benefit to society."

But controversy isn't new to Jay. When he began his web-facilitated, house call practice described above, Jay was investigated by the New York State Office of Professional Conduct.

"I knew I had plenty of haters given the heated debate in the medical blogs and news stories about my practice. I need to point out that I never once received any criticism from patients or the general public. The only criticism I've ever received came from within the medical community. So someone, somewhere called the state and complained...and given the online discussion I can only assume the complaint was made by a doctor."

The stage 3 tribe known as medical doctors has attempted to undercut other efforts as well. For example, some doctors now ask patients to sign "mutual privacy agreements" that transfer ownership of any public commentary the patients might write so that the doctors can censor their patient reviews if so desired. Of course, taking steps to have a nurse fired and lose her license to practice for educating a patient, as mentioned above, is another example of behavior against patient education and empowerment.

As I've written in my "nightmare" blog, I've made the committment to doing what I can so that others will not have to experience the kind of hell that I was forced to experience when dealing with the U.S. healthcare system. I appeal to all readers to get involved at least to the point of becoming an e-patient. I also ask you to share with me your ideas as to what else can be done -- what all I might do -- in the effort to meet that committment.

As an attendee of Health 2.0 San Francisco 2011 tweeted:

The time is ripe for a healthcare revolution -- an Occupy Healthcare movement -- a patient experience transformation. As Saul Kaplan stated in a Harvard Business Review blog:

"We need a new health care system that ... is designed for patients to champion their own pathways to wellness."

Everyone can play a role in achieving that change.

---

A duplicate of this posting appears in my "nightmare" blog.